by Adriano

The electoral season in Mozambique is open. On October 10th we are going to have the fifth municipal elections in the country. This election will decide who are the new decision– makers and solvers of the various problems that affect the 53 large and small cities and towns of Mozambique. The debates held so far in the run up to the elections are more directed to conventional politics: the transfers of members from one party to another, the exclusion by the National Election Commission of three candidates from the opposition side, the anecdotes about temporary adversarial linkages that weave behind the scenes of parties.

Although these discussions are part of the political process, they are focused on individuals and their interests rather than the visions, ideas, and proposals of what the newly elected officials will do to improve the quality of life of their residents. For the specific case of Maputo, I remember only a year ago when 17 people died in Hulene following an extreme flood event, when flood waters were exacerbated by unremoved solid waste. In February and March of this year we have seen the police forces monitor residents from Chiango who protested the government’s lack of solution to the floodwaters by blocking the new city’s ring road. Similar protest events occurred in Fomento e Liberdade neighborhoods in Matola Municipality. In the same rainy season, while conducing my PhD research, I visited residents of Chamanculo D struggling to get rid of rainwater flooding their homes and others fearing the risk that their latrines would collapse. I also observed various conflicts between residents over sanitation: who contributes or participates in the emptying of latrines, how they share the latrine between households who do not have the space or money for individual household toilets.

The time I spent in Chamanculo D drew my attention to absence of the issues of daily life – like sanitation and toilets – in the current political debates: we need to (re)politicize sanitation in Maputo city during this electoral hustle and bustle. During the electoral pre-campaign, politicians are rushing across the city to politicize a series of daily life issues related to infrastructure and service provision (transportation services, solid waste removal services, water supply services, electricity services), but sanitation is absent from the list of priority topics. In the current checklist of electoral prescriptions and promises, ideas and solutions for services delivery to better handle human waste and different versions of wastewater are being overlooked.

To highlight the unresolved challenges of sanitation, needing urgent attention from our political leaders and decision makers, I set out below seven statements on the challenges of sanitation facing Maputo. Many of these facts are not new, they have evolved over time, and many of them are well known by WASH sector stakeholders but without due attention. Other challenges of sanitation have passed unnoticed because they are seen as natural and part of our way of being and acting.

1. The municipality must recognize that the city is characterized by unequal access to sanitation services and wastewater infrastructures.

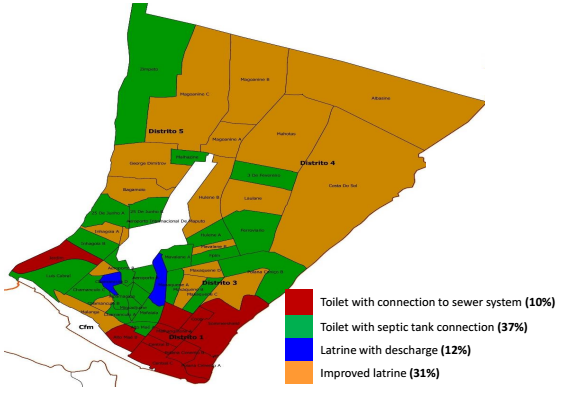

In present-day Maputo access to the infrastructure for collection, transportation and wastewater treatment is limited to specific spaces in the formally planned core of the city of cement. Only 10% of the municipal population is served by a sewage network, which covers less than 20% of the municipal territory and its functionality has been deficient for some years (WSP, 2014). This means that the vast majority of the city’s residents (90%) rely on their own facilities and infrastructures (typically latrines and septic tanks) to have adequate sanitation. Private operators are needed to empty these systems once they fill up and approximately 8% of all faecal sludge is transported by truck to the STP and emptied directly into the anaerobic ponds, being “effectively treated”. The historical analysis I conducted for my PhD shows that this picture of inequalities is rooted in the logic of colonial segregation and is still shape present policies and infrastructural development plans. The discourses on sanitation and hygiene of people in colonial times and their infrastructures were used to implant and develop a city characterized by exclusion, separation and segregation. Colonial authorities created racially distinct social statutes and used the topography and ecology of the place, and physical and spatial disposition of the city to produce these inequalities. The drainage system was prioritized for the city’s commercial centre and adjacent residential areas, while the rest of the city remained depended on septic tanks, latrines and bucket systems. All this was done at the detriment of the native populations that were destined to live in the low-lying and swampy suburb area, commonly known as the Zona das Lagoas (lagoon zone) that surrounded Xilungwine (white city).

Sanitation solution across the city. Source: AIAS, 2015

2. Urban planning needs to problematize this legacy and plans for sanitation must prioritize reducing these historical inequalities.

The colonial legacy of highly differentiated access to sanitation infrastructure and services presents a substantial challenge for current and future municipal authorities. But the debates I have had the opportunity to attend during the formulation of some of the city’s sanitation plans and the feedback on my own research findings from WaSH stakeholders reveal that the subject is not yet on the table, or even open for discussion. I observe that current policies and plans that continue to neglect sanitation for the poorest areas of the city. Current priorities for sanitation in the city are concerned with the conventional drainage network in the concrete city and new emerging affluent neighborhoods. These plans give the impression that sanitation is a problem only for one part of the city, the business district and the seaside town as the hub of real estate investments in form of skyscrapers and malls. This needs to change.

3. Infrastructure for collecting, storing, pumping and treating the city’s wastewater needs to be expanded, and existing infrastructure needs upgrading to stop further pollution of the Bay.

The city’s existing infrastructure system for collecting, transporting and treating wastewater has not been functional for 8 years. The sewage treatment plant works poorly. Sewage pumping stations which should convey the sewer to the treatment plant are not operational, which has been extensively covered before (e.g. here, here and here). They were rehabilitated but they failed again during the tests without having worked. This has resulted in the ongoing pollution of water streams and bay ecosystem as most of the sewage produced in the city is discharged directly into the bay, with all the imagined impacts. The main stakeholders framing the problem – municipality, the hired company and sanitary body – share the faults as evidence grows on the impact this situation has on the pollution of the environment and the bay. Although there has been little research done in this area of water pollution, there is convergence in acknowledging that sewage is key contaminant of the bay waters, since there is a growing evidence that the water inside the bay are polluted by untreated sewage coming from developing infrastructure that is not connected to the existing sewage and drainage facility and water treatment plant (Scarlet, 2015). This was also shown long before that groundwater contamination from pit latrines and storm water effluent is polluting the bay to the extent that swimming is inadvisable in all but the most distant areas of the bay (Louro, 2004). Therefore, operation and maintenance of infrastructures should also be part of the new municipal priorities.

Pumping stations for the sewer network. Source: Author.

4. Improving wastewater treatment needs to be linked to priorities for business development

Current private sector investments in high– rise buildings for offices, residential condominiums and shopping centers that we see flourishing in downtown and seaside areas of the city pose environmental sanitary challenges, since nobody (at the municipal level) know how all these buildings manage the sewage they produce. But they also pose challenges for investors. The recent closing of a well- known Shopping Center exemplifies the challenges posed by real estate boom to city sanitation. On 19th April this year, a Shopping Center located next to the Costa do Sol Beach was closed for ‘non-compliance with basic environmental management standards’. It reopened provisionally the next day after paying a fine of 500,000 meticais (8,000 USD) and guaranteeing that its wastewater treatment plant works. According to the general director of the National Agency for Environmental Quality Control (AQUA), the entity that ordered the closure of the facility, “the inspection team detected anomalies related to the mall’s treatment station that had not operated for over a year”. The media quoted the director stating that: “While the sewage treatment plant was inoperative the contents of the toilets were discharged directly into the sea without minimizing harmful impact on ecosystems and bathers’ health”. The building houses about 50 shops and 62 apartments of various types. This concern was not unfounded, since the images captured by the TVs newscast showed raw sewage coming out of the pipelines spreading through the mangrove fields and water streams surrounding the building complex. This wastewater was ‘waiting’ the high tide to naturally flow it to the sea/beach. Comments that followed in social networks (mainly Facebook) surprisingly revealed that the situation was not exclusive to that establishment. The comments converged in testifying that most of the backs of those beautiful buildings in the seaside area of the city hid veritable ‘rivers of faeces’ waiting also to be flowed into the bay.

This challenge is also a historical problem. All sanitation projects, plans, and masterplans drawn up since Lourenço Marques upgraded to the category of city – sanitation studies of 1887 and 1892, the General Sanitation Project (1955), the General Sanitation Scheme (1961), the General Sanitation Plan (1968), and the General Plan for Drainage and Sewage Treatment (1984) – opted for the same technical solution of making the bay and surrounding rivers and streams as the main outlet of all kind of wastewaters produced across the city. Even the new Sanitation and Drainage Masterplan for the metropolitan area of Maputo approved last year follows the same technical rationality, it suggests the construction of wastewater treatment plants in the vicinity of the bay and creeks (Costa do Sol, Infulene, Chiango, Katembe). Private sector real estate developers and the city council must be aligned so that the infrastructure component providing adequate sanitation (e.g. treatment and reuse) is considered in the design and approval of such projects.

5. Environmental and health impacts of city’s sanitation challenges, which are felt unequally by residents, need to be acknowledged, and addressed.

The new municipal authorities need to acknowledge, and deal with, the unequal environmental and health impacts of sanitation governance. Contemporary Maputo is huge inequality in access to services and exposure to certain environmental risks/pollutions of contaminated water. This means that even the malfunction of the wastewater infrastructures not felt by everyone in the city. Even assuming that all urban residents are affected, the environmental and health burden is unevenly distributed across the city. In 2017 Maputo was the scene of cholera outbreak that forced emergency measures. The cholera epidemic that was triggered by water restriction measures and heavy rains. The water crisis in Maputo and Matola causing people to resort to water sources that are not suitable for consumption. Cholera that has not been seen in the Mozambican capital since 2010 have occurred in four of the seven municipal districts – Ka Maxaquene, Ka Lhamanculo, Ka Mubukuane and Ka Mavota. The first two districts are the most critical in terms of sanitation in the city. They are in zones of high water table and crossed by open drainage channels that whenever it rains a lot water stagnates or overflow clogged by the rubbish. During this outbreak some water professionals with whom I spoke were reluctant to admit a link between the water crisis and the outbreak of cholera, always and anecdotally suggesting that cholera was a problem of lack of personal hygiene.

The history here is also partially called. Because of the specific spatial development of the city the political class or the elite neighbourhoods – the old “assimilated” Mozambicans and the nationalist elite who came from the suburb to replaced Portuguese citizens who left massively the city after independence – are not sufficiently exposed to contamination and any sanitation related problem, what could explain the ‘lack of political will’ to put urban sanitation as priority. Ecological and biophysical circulations of wastewater make residents of the affluent neighbourhoods not or less affected, because even without the full operation of the infrastructures actually the wastewater is drained to sewage or to the bay. This result of that original sociospatial arrangements made under the colonial sanitary planning, along with the topography of the city – a sort of inclined surface and sloping ramp up shape – which means that the wastewater of the elite, collected through the sewerage system, drains directly into the Bay (not treated) or naturally flows towards the low-lying and low-income suburban neighborhoods.

6. Sanitation improvement programs should prioritize the poorest neighborhoods in the city, which are most often in peri urban areas

The last challenge is the need to target the poorest and to make periurban sanitation one of the central axes of public services rendered by the Municipal Council of Maputo. The poorest of the city occupy the low income, unplanned peri-urban neighbourhoods, namely Chamanculo A, Chamanculo B, Chamanculo C, Chamanculo D, Malanga, Aeroporto A, Aeroporto B, Unidade 7, Munhuana, Mikadjuine, Xipamanine, Maxaquene A/B/C/D, , Mavalane A/B, Hulene A/B, Polana Canico A/B, Luis Cabral, Mafalala, and Inhagoia. They shelter about 80% of the population of the municipality of Maputo. These settlements are the ones that suffer the most from flooding resulting in frequent cholera outbreaks, widespread diarrheal disease and high child mortality, and and loss of assets and property. Interventions are being carried out by NGOs and CBOs, mainly the construction of shared sanitation facilities, promotion of the construction or improvement of household sanitation facilities, and supporting desludging service providers to provide hygienic, professional and commercially viable services. During my field work in rainy season (February and March this year) I had the opportunity to witness despite these acknowledged improvements, there are still people dwelling with floods whenever it rains and/or dwelling with shit every time the latrine fills up for not having the enough money to pay the emptying of their toilet. The sanitation of the poor is getting worse since current policy suggests a governmental retreat from the direct provision of services and by placing most responsibility for organizing and paying for their own sanitation services on those urban residents who can least afford. This whole scenario is compounded by an unfavourable context of a country’s monetary austerity, since Mozambique is grappling with a financial and debt crisis. All this to say that the battle against the urban poverty must return to be part of the actions of municipal government, as it is shaping the people capability to ensuring that new and existing pit toilets are emptied and faecal waste is disposed safely.

Shared latrines in Chamanculo D. Source: Author.

7. Maputo’s citizens should be involved in the search for solutions

The involvement of civil society in the debate on sanitation issues is very limited. There are in fact few organizations of civil society in Mozambique and Maputo specifically intervening in matters of water, sanitation and hygiene in the capital. Civil society groups should set up platforms for debating and advocating such kind of topics. Civil society cannot only wait on the proposals of politicians, it can organize itself to also influence and nourish the agenda of politicians. Sanitation is linked to nutrition, is connected to gender-based issues, such as violence. It impacts also on access and retention of girls in schools. There are several entry points that can be used to bring this holistic topic at the debate table. As electorate we are all called to make sure that sanitation issues are spotlighted, they are raised in debates, and inserted into the list of topics for radio and TV talk shows as well as in our daily interactions with the Chefe do Quarteirão in ours neighbourhoods. This is our counterpart in terms of responsibility as voters.

References

-

- Bandeira, S. and Paula, J. (eds.). 2014. The Maputo Bay Ecosystem. WIOMSA, Zanzibar Town, 427 pp.

- Kronkvist, B. (2006). Prevalence of faecal indicator organisms and human bacterial pathogens in bivalves from Maputo Bay, Mozambique.

- Louro, C. M. M. & M. A. M. Pereira (2004). Avaliação preliminar da poluição microbiológica na Baíade Maputo. Relatório de Investigação No 1: 9 pp. Maputo, Centro Terra Viva

- WSP 2014. Caracterização do Saneamento em Maputo. Maputo, Agosto de 2014. Maputo: Banco Mundial.

- Scarlet, Maria Perpétua. (2015). Biomarkers for assessing benthic pollution impacts in a subtropical estuary, Mozambique.